Changes in retail encourage walkable urban designs

Retail in Walkable Neighborhoods

For many years, retailers resisted the architecture of street-facing storefronts, but necessity is the mother of flexibility.

For many years, retailers resisted the architecture of street-facing storefronts, but necessity is the mother of flexibility.This is one of a series of ongoing Public Square articles on the market, technological, and cultural transformation of the $5 trillion retail industry—and how it relates to a continued shift toward walkable, urban living.

When America switched from urban downtowns and main streets to suburban shopping centers and malls, the retail industry dramatically changed the design of its buildings and storefronts. Stores, especially the chains, became standardized as boxes fronted by parking lots in stand-alone stores, shopping centers, and malls.

Compared to the downtown mixed-use buildings, the quality of design plummeted with these automobile-oriented formats. And, the chain stores tended to look more or less the same. If you have seen one commercial-strip CVS, Taco Bell, AutoZone, or Walmart, you have seen them all.

Breaking out of that automobile-oriented design system has proven very difficult—but we may have turned a corner in the last few years.

Not long ago, getting a decent urban store often required extraordinary determination—especially in suburban locations. Mashpee Commons in Mashpee, Massachusetts, for example, is the nation’s first suburban retrofit project, and it began to achieve strong sales in the 1990s. CVS wanted to locate there and proposed a standard design with the parking in front. Developer Cornish Associates insisted that they meet the traditional neighborhood design standards, and CVS declined, only to come back several years later with the same proposal. Cornish turned them down again. In the early 2000s, CVS agreed to build a unique “main street” store, which generated unusually high sales and the store is still successfully operating. CVS—which is now the nation’s seventh largest retailer—could not be forced to change, but they were motivated to try something new in the case of Mashpee Commons, and the developer had the strength of conviction to wait them out.

Back then, CVS had little experience designing and building stores in walkable urban places—but the chain has more experience today. It is now an industry leader in urban pharmacies.

Two major changes have encouraged retailers to be more flexible. First, the shopping center industry, particularly enclosed malls, is in trouble. Media stories of a “retail apocalypse” put the fear of God in corporate managers, encouraging them to “think outside the box”—literally, in the case of store design. Public Square has reported that the retail apocalypse is greatly exaggerated, yet department stores and apparel tenants of suburban malls are closing at an alarming rate.

Two major changes have encouraged retailers to be more flexible. First, the shopping center industry, particularly enclosed malls, is in trouble. Media stories of a “retail apocalypse” put the fear of God in corporate managers, encouraging them to “think outside the box”—literally, in the case of store design. Public Square has reported that the retail apocalypse is greatly exaggerated, yet department stores and apparel tenants of suburban malls are closing at an alarming rate.

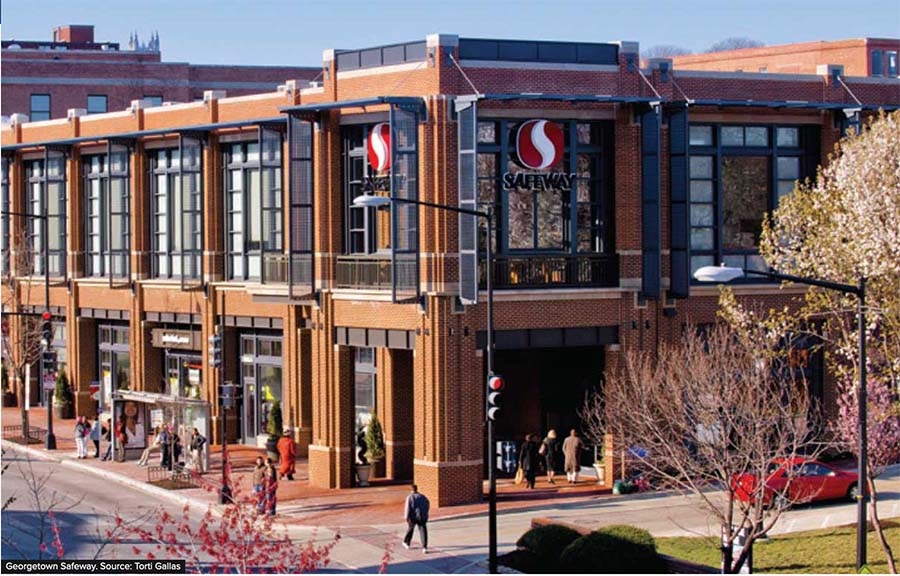

Second, cities and urban centers, which are attracting the middle and professional classes with disposable income, are a growing market for retailers. Downtowns are generally under-retailed. “Many cities have less than 5 square feet per capita versus 22 square feet nationally and 70-plus square feet in many suburbs,” according to urban planner and retail expert Robert Gibbs. “The cities represent the best growth option for most retailers.” Many retailers are seeking locations with 80-plus Walk Scores, and are changing their store designs accordingly. While a great deal of standardization remains—with signage, marketing, store layout, technical systems, and operations—the urban context demands a more individualized and context-sensitive approach to design. A good example from early in this decade is the Safeway in Georgetown, DC, a 2012 Charter Award winner for architect Torti Gallas (see top photo).

The Safeway—a brand of the nation’s second-largest grocer—is a two-story supermarket brought to the street. The pedestrian-friendly building hides its garage below the building. The redesigned building employs a compact height to fit in with an adjacent park.

To ensure easy access for pedestrians to the supermarket, three ground-level entrances are offered through two active sides of storefronts and one semi-active side of the building—along with a corner entrance.

The historic context of the site calls for sensitivity in designing the exterior of the market—and the design team responded by a thorough study of historic public market styles and was attentive to details. The subtle differences of every bay of the Western Wisconsin Avenue façade reflect the nuanced adaptations of Georgetown’s buildings over time, while the use of red brick fits in with the historic neighborhood.

H&M, a trendy clothing retailer and the second largest internationally, recently opened a 25,000-square-foot store on Woodward Avenue in downtown Detroit, locating in a continuous storefront that occupies the first floor of three historic buildings. H&M is placing stores in a number of downtowns and walkable urban centers in the suburbs—such as Pike & Rose in Rockville, Maryland, and the Streets at Southglenn in Centennial, Colorado.

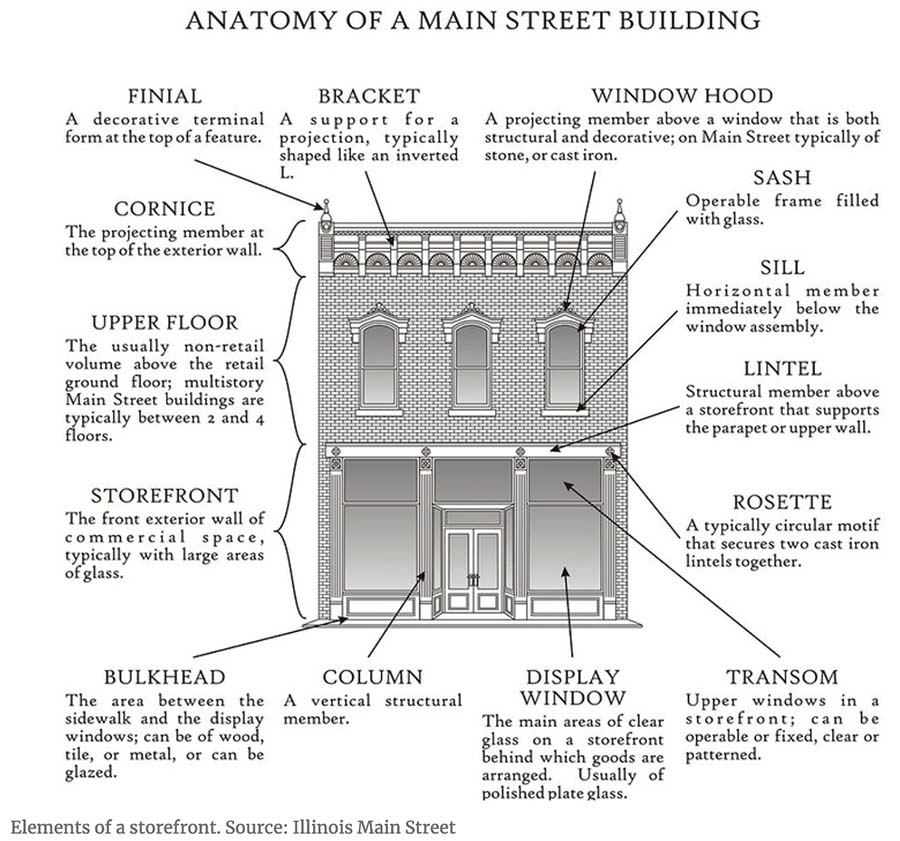

Most urban format stores don’t go to the design or historic renovation lengths of the Georgetown Safeway or the Detroit H&M, but they use flexible formats that meet the street like traditional main street stores. Retailers have to become familiar with the basic elements of storefronts—knowledge that was once common. Designs don’t have to be traditional, like the example below, but they include similar elements, which can be scaled up for larger stores.

Most urban format stores don’t go to the design or historic renovation lengths of the Georgetown Safeway or the Detroit H&M, but they use flexible formats that meet the street like traditional main street stores. Retailers have to become familiar with the basic elements of storefronts—knowledge that was once common. Designs don’t have to be traditional, like the example below, but they include similar elements, which can be scaled up for larger stores.

Nearly all of Target’s openings since 2016 have been small-format urban stores. Target, the eighth largest US retailer, has increased its revenue, earnings, and assets every year since. These stores don’t just have different urban design—they have different merchandise and store layouts. Toilet paper may be sold in single rolls rather than in bulk. The automotive section may be eliminated. This points to another reality of urban stores—the business model shifts. The stores tend to be smaller—and have higher sales per square foot. Retailers may need to get comfortable with a new business model in addition to greater design flexibility.

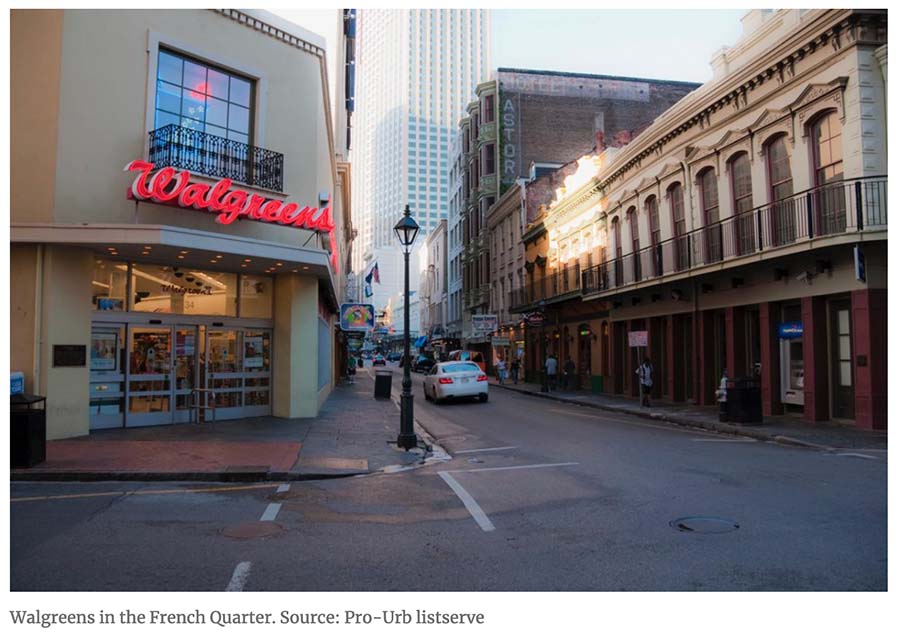

Office Depot also has an urban strategy, opening stores with one-fifth the store space and half the usual items in urban locations. 7-11 is expanding with 2000-square-foot urban neighborhood markets. National chain drugstores like CVS and Walgreen’s—the fifth largest US retailer—have opened many walkable urban stores in recent years.

Giant supermarket is aggressively expanding in Philadelphia. It has already opened two of its small-format Heirloom Markets, and is opening two more. In the second half of the 20th Century, retail buildings grew progressively larger as they located along massive arterial roads in the suburbs. Now that process is reversing itself. “For a variety of reasons, big grocery companies think it’s worth a shot to shift small,” according to Moneymagazine. “For one thing, whereas megastores typically require an undeveloped suburban location, smaller stores can fit almost anywhere, including densely populated cities, college towns, and even college campuses.”

Architect Seth Harry offers an example of a change in attitude among grocery chains: “Ten years ago, I was asked by a faith-based community developer to help persuade a major Midwest retailer to build a small, urban grocery in Grand Rapids, Michigan, as part of an infill mixed-use, affordable housing project they were developing. Until then, the retailer had only built ‘super centers’ that competed directly with super Walmarts, and only in suburban locations. At the time, they were persuaded of the potential of a smaller urban format, but said they weren’t yet ready to go there. However, that store is now built, and I recently visited it. They did a spectacular job.”

Architect Seth Harry offers an example of a change in attitude among grocery chains: “Ten years ago, I was asked by a faith-based community developer to help persuade a major Midwest retailer to build a small, urban grocery in Grand Rapids, Michigan, as part of an infill mixed-use, affordable housing project they were developing. Until then, the retailer had only built ‘super centers’ that competed directly with super Walmarts, and only in suburban locations. At the time, they were persuaded of the potential of a smaller urban format, but said they weren’t yet ready to go there. However, that store is now built, and I recently visited it. They did a spectacular job.”

Trader Joe’s, a small-format grocery store averaging 10,000-15,000 square feet, has been expanding nationwide. The store has the highest sales per square foot in the industry, and in 2019 it ranked number one in customer preference. The small size allows it to located in urban and suburban settings alike. Grocery stores are important retailers downtown—they increase sales of surrounding retailers by as much as 25 percent—and provide the kind of retail, like pharmacies, that people need day-to-day.

There have been bumps along the road. Not all of smaller-format stores have been successful: Walmart’s small-store “express” format was a failure. It closed all 102 of them in 2016. Walmart’s small-format stores were automobile-oriented suburban designs—basically their big stores shrunk down, with surface parking in the front. “Walmart’s tiny stores were mostly located in the suburbs and poorly populated areas, Target is targeting territory that’s loaded with foot traffic,” notes Money.

Another challenge is the ownership of buildings, according to Gibbs. Retailers like Kohl’s or TJ Maxx require owners to invest substantial sums before they will locate in historic buildings, notes Gibbs. “Many of the downtown property owners would rather get low rent than pay that $300,000 to prepare the building.”Nevertheless, there are so many urban storefronts that retailers will find sites.

Even Ikea has been opening up urban stores. “Most large format retailers are focusing on urban centers for their growth and are flexible with their standard formats if the city has strong design standards,” Gibbs says.