Walkable Neighborhoods

We Want More Walkable Neighborhoods — but Can Our Communities Deliver?

“The most requested neighborhood characteristic of all buyers is walkability,” real estate broker Andrea Evers recently told a reporter for The Washington Post. But, in an article written by the Post‘s Michele Lerner, Evers went on to say that “very few areas” in the greater DC market meet the desired criterion, particularly if the prospective buyer wants to be within walking distance of a Metro transit station. And that, in a nutshell, is the good and bad news of walkability.

Let’s elaborate on the good part: More and more of us want to be within safe and comfortable walking distance of the destinations that meet our everyday needs, such as shops, places to eat, services, parks, and good transportation options that can take us downtown and to jobs and other places we want to go. It’s the hottest trend in real estate, sought by buyers and renters alike.

The demand is increasing

In fact, demand for walkable neighborhoods is only going to increase, as more and more members of the millennial generation, the largest generation in American history, enter the home-seeking market. Millennials prefer urban amenities more than their predecessors: 50 percent consider it “very important” to be within an easy walk of places “such as shops, cafes and restaurants,” according to the results of a nationwide survey released earlier this year by the National Association of Realtors and Portland State University. Among baby boomers, the portion considering walkability to be very important is 38 percent.

Earlier survey research (reported, for example, here) has found that 31 percent of millennials want to live in a core city, as opposed to only 15 percent of baby boomers and 18 percent of generation X. (Forty-two percent of millennials prefer living in a suburb, and 25 percent prefer living in a small town or rural setting.) But, even if they want to live in a suburb, most millennials still want walkability; 71 percent of all millennials reportedly want their home neighborhood to be walkable. Moreover, seventy-eight percent are looking for diversity; this is a generation that grew up with more diversity than its predecessors and has come to expect it where they live, in housing types and in the incomes and ethnicity of their neighbors.

It’s not just millennials who are driving demand for walkable neighborhoods, of course. In addition, a large number of baby boomers – the second largest generation in American history – are seeking new places to live as they downsize, and many of them, too, want to be able to walk to shops and amenities. Also writing in The Washington Post, reporter Ylan Q. Mui put it this way:

“Roughly 10,000 baby boomers are retiring each day, and recent data show that half of those who plan to move will downsize when they do. Many are seeking the type of urban living that typically has been associated with young college graduates — so much so that boomers are renting apartments and buying condos at more than twice the rate of their millennial children.”

Two recent articles in The New York Times frame the increasing demand for walkability nicely: In one, reporter Robert Strauss relates the stories of several affluent families who have recently moved from large homes in the suburbs into upscale high-rises in downtown Philadelphia, Atlanta, Boston and Washington, to take advantage of all the amenities at their doorsteps. In the other, David Zweig writes about his young family’s move from highly urban Brooklyn to a suburb, albeit an older one that accommodates their preference for a walkable lifestyle.

Zweig, who is 41, moved with his wife and two small children to Hastings, New York, after considering the charming but less walkable Croton-on-Hudson. He describes the choice between the two communities:

“After several tortured visits, we passed on the place [in Croton] because of the longer commute and its isolation. Though we weren’t looking for a bustling city center, the downtown was too limited. And we would have had to drive everywhere — to the train, to friends’ houses, stores. Being able to walk places was a priority.

“Houses in Hastings, even the larger ones, tend to be on relatively small lots. Not only does this encourage more walking, but seeing my neighbors 20 feet away having an evening drink on their front porch or the children across the street playing on a lawn creates a communal environment that many suburbs, let alone exurbs, don’t have.”

Across all generations, the Realtors/Portland State survey found that an overwhelming majority of respondents – 79 percent – believe it to be very or somewhat important, in choosing a home, to be “within an easy walk of other places and things in the community.” It also found that people who now live in such neighborhoods are especially satisfied with the quality of life in their communities. Fifty-four percent of those respondents who agreed with the statement “there are lots of places to walk nearby, such as shops, cafes, and restaurants” reported being very satisfied with the quality of life in their communities; only 41 percent of all respondents reported being very satisfied.

The survey also found that “many people want to live in a more walkable neighborhood than they do now. Overall, 25 percent currently live in a detached, single-family home, but [when presented with the choice] would prefer to live in an attached home in a neighborhood where they could walk to places and have a shorter commute.”

What makes a neighborhood walkable?

So what is a walkable neighborhood, anyway? What are the physical characteristics of a community that invite people to walk? Well, a lot of things matter, from the presence of street trees to perceptions about safety to the size and positioning of buildings (and their entrances) on the street. Take a look at the “walkable streets” sections of the green rating system LEED for Neighborhood Development, or at Victor Dover and John Massengale’s epic book Street Design (I contributed a very small passage to that very large work) for the wide range of relevant topics.

I’ve been reading everything I can find on the topic for the last two decades. And, while lots of factors influence walking to one degree or another, three attributes jump out of the research as particularly and demonstrably relevant:

– Well-connected streets. The smaller the block size, and the more intersections, the better. This makes potential travel routes shorter, more direct, and frequently safer, since well-connected neighborhood streets can provide quieter alternatives to walking along high-speed arterial roads. Reid Ewing and Robert Cervero’s definitive study of how land use affects travel behavior (actually a quantitative – and exhaustive – study of studies) found that the degree of connectivity in a neighborhood is statistically the most significant indicator of how much walking takes place there.

– Things to walk to. Simply put, peoplewalk more when they have places they want to go within walking distance. Research has also shown that people who live in neighborhoods where homes are accessible to shopping walk more and actually weigh less, on average, than residents of automobile-dependent neighborhoods, even when other potentially relevant factors such as age, income, and ethnicity are discounted in the analysis.

– Good infrastructure for safe walking. Sidewalks are important, as well as safe street crossings and nearby motor vehicle traffic moving at nonthreatening speeds.

Fortunately, most metro areas in the US do have walkable neighborhoods that match these characteristics, along with the other attributes now ascendant in the market. But the bad news is that there aren’t enough of them to meet demand, and very, very few of them are new. With limited exceptions, walkable neighborhoods in this country tend to be found mainly in inner cities and older residential areas built before World War Two. And, because their supply is limited, prices for walkable locations are sky-high. Research has shown that each one-point increase in a home’s Walk Score (a 100-point scale measuring an address’s accessibility to walkable destinations) is associated with a $700 to $3000 increase in its value compared to less walkable homes of comparable size.

Why the scarcity?

The problem is that, although walkability is highly valued today, it was not a commonly sought-after characteristic in the latter half of the 20th century, when much of our existing housing stock was built. At the time, roads and parking lots were less congested, driving everywhere seemed more of a convenience than a challenge, and the portion of the housing market seeking urban amenities was shrinking. The portion wanting to get away from it all, and willing to undertake long commutes to do so, was dominant. The homebuilding industry settled into a pattern of building internally pleasant but uniform subdivisions farther and farther from city centers, frequently without sidewalks, with nothing but other, near-identical houses within safe walking distance, and connected to the rest of civilization only by busy arterial roads lined mainly with strip shopping “centers,” large parking lots, drive-through businesses, and gas stations.

That model still works for a portion of the market, but not the portion that is growing.

Nonetheless, the model remains prevalent. Communities wishing to build walkable neighborhoods or retrofit old ones to be more welcoming and useful to pedestrians face an array of challenges, from lending practices that favor conventional suburban development based on automobile-first design to outdated zoning and regulatory schemes that effectively prohibit things like corner stores mixed with residences, a diversity of housing types in the same development, and pedestrian-first design that places building entrances closer to sidewalks.

While historic neighborhoods and other older but now “nonconforming” walkable development are essentially “grandfathered” in, plans for new construction that seek to mimic those older neighborhoods can seldom be permitted as a matter of right; instead, they must face a gauntlet of legal and procedural hurdles in order to obtain variances and special permissions. This makes the entitlement process for walkability more lengthy, expensive, and uncertain, assuring that in most communities it will remain the exception, not the rule. In the words of Atlanta architect Eric Bethany, “most current zoning ordinances are a combination of good intentions producing bad outcomes for most places.”

What to do

Fortunately, many communities wishing to update their regulatory processes to accommodate twenty-first century neighborhood preferences are turning to zoning reform, replacing outdated “use-based” codes with “form-based” zoning. The distinction is important: Use-based codes deliberately separate different kinds of residential buildings from each other and, typically, forbid all commercial uses in residential zones. This practice made a certain amount of sense when it was initiated, separating, for example, polluting factories from housing and playgrounds. The separation of such obviously conflicting uses still makes sense. But, today, many more commercial uses are fully compatible with residential ones and neighborhoods with a gentle mix of complementary uses are well aligned with market preferences.

Form-based codes, by contrast, de-emphasize the regulation of building uses and focus instead on the size and positioning of buildings and their physical relationship to each other and to public spaces such as streets and sidewalks. As the Form-Based Codes Institute puts it, building form standards regulate things such as “how far buildings are from sidewalks, how much window area at minimum a building must have, how tall it is in relation to the width of the street, how accessible and welcoming front entrances are, and where a building’s parking goes.” The idea is to create rather than inhibit a walk-friendly environment.

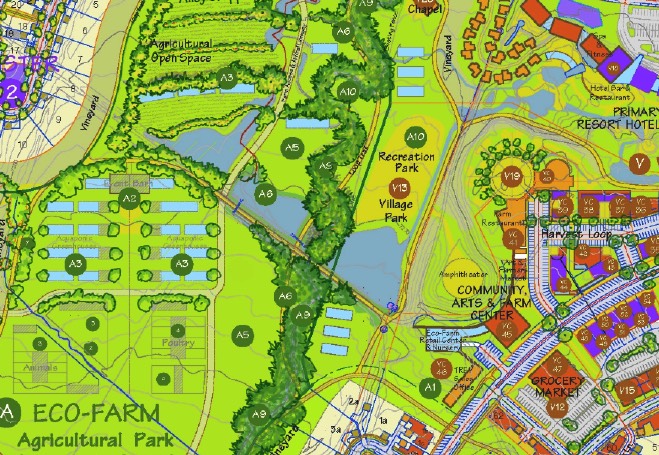

There is a great deal of variation among specific form-based codes, but many attempt to match appropriate building form standards to particular types of neighborhoods depending in significant part on where they fall along the rural-to-urban “transect” developed initially by New Urbanist planners, architects and thought leaders Duany Plater-Zyberk & Company. (See, in particular, the open-sourced “SmartCode” created by DPZ.) While some form-based codes are applicable across an entire municipality, others apply only to designated places within a community that are ripe for walkable development. Sarasota County, Florida, for example, offers its form-based code to “planned mixed-use infill” if a proposal “incorporates the principles of traditional neighborhood design” including, among other things, well-connected streets, high-quality public spaces, compact development, and a diversity of land uses.

My PlaceMakers colleague Hazel Borys and Arizona State University’s Emily Talen have been tracking the adoption of form-based codes worldwide. As of early 2015, they had documented nearly 600 codes incorporating form-based criteria, over half of which have been fully adopted. Big cities in the US that have employed form-based codes include Miami, Nashville, Dallas, Ft. Worth, Denver, Albuquerque, Cincinnati, and many others, though “form-based codes have also been applied to as small as 100-person populations and 35 acres,” report the two researchers. (The Form-Based Codes Institute also maintains a searchable database of codes.)

LEED-ND as a policy tool

LEED for Neighborhood Development, or LEED-ND, offers another set of standards for updating zoning and other regulatory barriers that stand in the way of creating more walkable neighborhoods. In particular, LEED-ND establishes criteria for development that prioritizes things like access to shops and services, streets and sidewalks that interface with buildings to create a comfortable walking environment, transit access, efficient use of land, affordable housing, and environmentally sensitive building practices. Planned or built development meeting the system’s set of prerequisites and optional credits are “rated” and, if they qualify, rewarded with certification at the certified, silver, gold, or platinum level.

The creators of the system – the Natural Resources Defense Council, the Congress for the New Urbanism, and the system’s current owner and administrator, the US Green Building Council – devised LEED-ND both to reward developers who pursue green development and to serve as a model for local governments to borrow from in creating their own standards. The system is comprehensive, comprising 53 base categories of criteria ranging across three basic groupings including development location and linkage, neighborhood pattern and design, and green infrastructure and buildings, plus additional “above and beyond” credits for innovation and responsiveness to regional concerns.

As a result, LEED-ND makes a terrific audit tool for evaluating a jurisdiction’s development policies and programs. The city of Ithaca, New York, for example, hired the Agora Group’s president Jessica Cogan Millman to do just that in 2013, as it was updating its comprehensive plan. Millman partnered with the Natural Resources Defense Council and Criterion Planners to undertake an extensive “sustainability audit” of a suite of ten important policy instruments including, among others, Ithaca’s zoning code, site plan review ordinance, stormwater management regulations, subdivision regulations, transportation planning documents, and capital improvement plan. The result was a 277-page set of recommendations for aligning Ithaca’s policies and planning with the goals and standards of LEED-ND. Those recommendations are now in various stages of implementation and consideration.

Other jurisdictions that have applied the rating system to update their policies or address development needs in specific neighborhoods include – to name just a few – Las Vegas, Nevada; Babylon, New York; Bellingham, Washington; Cheyenne, Wyoming; Champaign, Illinois; Boston, Massachusetts; and Austin, Texas.

There are a number of resources available to local governments wishing to use LEED-ND to reform their codes and policies to produce more walkable, greener neighborhoods. Criterion Planners, in particular, has developed a “Local Planners Catalog of LEED-ND Measures,” essentially a restatement of the rating system into a local planning and coding framework more familiar to municipal planners than the standard LEED taxonomy; its categories include planning process, land use, transportation, resource protection, buildings, site development, and public facilities and services. Criterion also has a “LEED-ND Community Audit Checklist,” a version of which was used in the Ithaca review, tracking the same categories.

In addition, the Land Use Law Center at Pace University has produced a “Technical Guidance Manual for Sustainable Neighborhoods,” drawing from the experience of some 60 municipalities that have used LEED-ND in planning, zoning and policy, and intended for use by local governments interested in promoting greener development. The Center has also created a model zoning framework based on LEED-ND that can be used to establish a “floating zone” to supplement a community’s standard zoning and be applied as desired to specific neighborhoods well-suited to the use of LEED-ND principles.

With demand already strong, and demographics poised to make it even stronger, walkable neighborhoods will continue to gain favor both in the marketplace and on the ground. That is great news for the environment, since the result will be reduced automotive emissions, increased public health because of greater physical fitness, and reduced increments of suburban sprawl.

It is encouraging that many communities are taking steps to enable walkable development, and that tools are being created and implemented to help them do so. But the Land Use Law Center estimates that there are some 40,000 local governments in place around the country, and regulatory barriers to walkability remain in place in most of them. That’s a lot of catching up to do.